Blog Post II: Charles Robinson's Scandalous Marriage

Joanna Barker, Elizabeth Montagu's Correspondence Online

What is Charles Robinson hiding? Elizabeth Montagu’s youngest brother, Charles Robinson, is a quiet figure in his sister’s letters. He doesn’t share a voluminous correspondence with her, like Sarah Scott, or receive beautiful, lyrical descriptions of the Scottish highlands, like Mary Richardson. He appears only fleetingly, in a patchy string of functional missives scattered between more significant correspondents. Behind and around this minor figure, however, section editor and project manager Joanna Barker has found a scandal which reveals that his muted presence in the archive may be concealing a well-kept family secret.

Charles Robinson (1732-1807) was Elizabeth Montagu’s youngest brother. His mother died when he was fourteen, and he was first put into the Navy like his older brother Robert (1717-1756), but gave this up and followed his brothers Morris and Thomas into the law. He entered Middle Temple in 1749 and was called to the bar in 1753. He had a successful legal career: in 1763 he became Recorder of Canterbury; to which in 1766 he added the positions of Recorder of Hythe, New Romney and Sandwich, and in 1770 that of Recorder of Dover. He was also a bankruptcy commissioner from 1766 to 1792.

© Art UK

Towards the end of his life, Charles Robinson’s portrait was painted by Stephen Hewson, and after his death it was hung in the Guildhall in Canterbury.

Charles was elected one of the two MPs for Canterbury in the 1780 and 1784 elections, his eldest brother Matthew Robinson Morris (1713-1800) having held the seat from 1754-1761. He served the town for ten years but made little impact in parliament (only two speeches have been recorded), and declined to stand again in 1790. In 1776 he was known in Kent as a respected middle-aged bachelor and professional man.

But in April of that year a mysterious anonymous letter was received by Elizabeth Montagu. The writer imparted the information that her brother Charles was secretly married, and had a daughter who was now eighteen years old. Even more extraordinary was the news that his wife was the sister of the wife of another of her brothers, Morris Robinson. At first Montagu gave no credit to this claim, but when she confronted Morris with the information he admitted it was true, while begging her to keep it secret so Charles could announce it himself.

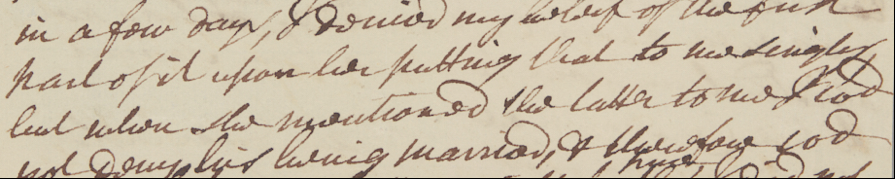

My Sister Scott leaving recounted an speculation in a letter from her friend Mr Blount, that Charles was sudden to be married or declared to be married in a few days, I denied my knowledge of the first part of it upon the putting that to me singular but when she mentioned the latter to me I cd not Deny his being married…I had been obliged in Consideration with you a little while before you left town to acknowledge his being married, but that I had desired you not to maintain it till he thought proper to disclose it himself.

Morris Robinson to Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, 29 April 1766, Huntington Library, MO 4789

Charles, however was curiously reluctant to make this announcement, and rumours started to run round Canterbury, which Montagu described as “ye most tittle tattle Town & Neighbourhood in ye Kingdom”. She advised that the newly-discovered Mrs Robinson should show her marriage certificate to a neighbour, in order to put a stop to the supposition that their relationship was irregular and their daughter illegitimate.

Mrs Charles Robinson shd show to some creditable friend of hers at Canterbury ye certificate of her marriage. I do not mean that I have any doubt of it, or wd look at ye certificate, but ye Girl having worn another name it might be right to silence ye malice & tittle tattle of ye most tittle tattle Town & Neighbourhood in ye Kingdom.

Elizabeth Montagu to Morris Robinson, 4 May 1776, MO 4805

Despite her protests, adultery had been Montagu’s own assumption when she first heard the news: she told her sister Sarah Scott that she had thought it to be “an affair for which a man does penance only once in a white sheet” (the traditional punishment for adultery), but since he was married “it seems it is of that sort for which a man does penance all his life”:

I took my temper at last, thinking ye letter misrepresented ye case & that it does penance only once in a white sheet, but it seems it is of that sort for which a Man does penance all his Life.

Elizabeth Montagu to Sarah Scott, 2 May 1776, MO 5986

So who was the mysterious Mrs Robinson? Mary Greenland was the youngest of the three children of John Greenland (1690-1744) and his wife Jane Batchelor. The family lived at Lovelace in the parish of Bethersden in Kent; Mary’s brother Augustine Greenland was an attorney like her brother Morris, but the Robinson family considered them to be their social inferiors. (Montagu referred to Charles as “marrying ill”, and her sister-in-law Mary Robinson, wife of her brother William, regarded their marriage as an “improper connection”.)

On 28th April 1748, at the age of nineteen, Mary married Richard Dawkes (1719-1755). He came from an established Dover family: one of his ancestors, also named Richard Dawkes, had led a group of Parliamentarians who captured Dover Castle in 1642. They had five children, but only two daughters survived infancy. Richard Dawkes died in Dover in 1755, leaving Mary as a 26-year-old widow with two young children. She was by no means destitute, since her husband had settled on her for life the estate of Maxton in Dover that he had inherited from his father.

Two years later, on 13th February 1757, Mary’s sister Jane Greenland married Morris Robinson in Bath: their witnesses were Charles Robinson and Sarah Scott. Elizabeth Montagu and Sarah Scott never liked their sister-in-law: they regarded her as spendthrift and too interested in living a fashionable life in London that her husband, a lowly attorney in the Chancery office, could ill afford. Montagu was later to observe, after Morris’ death in 1777, of the match that “there is no end of ye bad consequences of an improper marriage”:

I pity her extreamly, but certainly he loved expence better than he did. I imagine poor Man, he thought her fine dress & appearance raised her in the eye of the World. There is no end of ye bad consequences of an improper marriage.

Elizabeth Montagu to Mary Robinson, 9 January 1778, British Library Add MS 40663, f. 69-72

It must have been about this time that Mary Dawkes secretly married Charles Robinson. The exact date of their marriage is unknown, as is the date of birth of their daughter Sarah. If Mary did show her marriage certificate to a friend, the document has not survived, and since they wished to disguise their relationship, it is likely they had Sarah baptised in some London church rather than in Kent. Sarah died in 1839, and her memorial tablet says she was “in her 81st year”, so this would mean she was born in 1758. Montagu referred to the fact that the girl had “worn another name”, and the only name she could have borne respectably was Dawkes, so Mary must have remained silent about the paternity of the child to whom she gave birth three years after her husband had died.

Montagu regarded it as being to Mary’s credit that she had not made her marriage to Charles public until she needed to protect her daughter’s interests. In 1776, when the news came out, Sarah would have been eighteen and considered as being of marriageable age. Her prospects would be much enhanced if she were known to be not the suspiciously young daughter of a deceased gentleman from Dover but the only child of the respected Recorder of Canterbury and the niece of the celebrated Mrs Montagu and of Matthew Robinson, heir to the title of Baron Rokeby. One cannot help wondering if Mary herself was the author of the anonymous letter that betrayed the secret. Montagu clearly felt that the affair was a humiliation to the whole family:

When I think of the vanity & pride with which I once used to appear at Canterbury Races where our Father & Mother were ye envy of every body, & think of ye figure the family makes at present, it strikes me deeply.

Elizabeth Montagu to Sarah Scott, 2 May 1776, MO 5986

The anxious sister tried to excuse Charles on the grounds that he was “a mere boy” when he contracted his marriage, and did not have the “protection of a Father & Mother & a creditable home”. This is a little disingenuous, since her brother must have been twenty-five at the time.

Montagu hoped for the best, saying of Mary that “I believe she is a good sort of woman” and “I shall behave with great civility to them, & act with friendship”. She was sympathetic towards her newly-acquired niece, being aware that her situation was not her fault. If she blamed anyone it was Morris who, by marrying one of the Greenland girls, had made it seem to Charles that he could marry the other. Having become reconciled to the situation, she turned it into a joke, saying to Sarah Scott that she hoped their eldest brother Matthew, who was known for his long hair and wild beard, would marry “some fair Dalilah of ye Philistines who will cut off his hair that ye family may get some credit back again”.

Mary Robinson, the wife of Montagu’s brother William, also hoped for the best, sincerely wishing that Charles might “live comfortably in his new assum’d character”. She assured Montagu that when she and her husband returned to town, they would “pay proper compliments to the Lady & Daughter”. She did, however, urge Montagu to take steps to prevent this situation from occurring again:

Pray can you give me any Receipt to prevent the like happening again in the next generation, do pray at your leisure write a Treatise on the disadvantages of improper Connections for the benefit of your Nephew, & Nieces.

Mary Robinson to Elizabeth Montagu, 27 May 1776, MO 4743

In fact, the marriage seems to have turned out well, and the scandal does not appear to have damaged Sarah Robinson’s prospects. On 15th August 1780, she married William Hougham (1752-1828), from a leading Canterbury family. They lived at Barton Court in Canterbury, a property first purchased in 1657 by their wealthy ancestor Sir Solomon Hougham, a goldsmith. William’s father rebuilt it in the form in which it survives today and gave it to his son as a wedding present.

Sarah Hougham spent the last eleven years of her life as a wealthy widow, having inherited the estates of her “late most beloved father” Charles Robinson and her husband William Hougham. She had no children, and left most of her estate to the descendants of her mother’s first marriage. The only member of her father’s family to receive a bequest was Henry Montagu (1798-1883), who was the second surviving son of Matthew Montagu and succeeded his brother Edward as the sixth and last Baron Rokeby.

All Manuscript Images are taken from the Elizabeth Montagu Papers (MO), held at The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, digitised as part of the Elizabeth Montagu’s Correspondence Online project.

Please note that all dates and location information are provisional, initially taken from the library and archive catalogues. As our section editors continue to work through the material we will update our database and the changes will be reflected across the edition.

Browser support: The website works best using the Chrome, Edge, and Firefox browsers on the PC, and only Chrome and Firefox on the Mac.