The Indian Connection I

Joanna Barker

On 12th July 1785, Elizabeth Montagu proudly described to her sister-in-law Mary Robinson the wedding day of her nephew and heir Matthew Montagu to Elizabeth Charlton. She regarded the match as largely her own achievement, and happily noted that ‘the decent dignity of the Brides behaviour, & the delicacy of the Bridegrooms did them honour, & gave me great pleasure, & we are three as happy people as can be found in any part of the habitable Globe’. She had in previous letters referred to her negotiations with the young lady’s guardians, including her grandmother Mrs Frances Southby. Miss Charlton was only nineteen years old and was an orphan, but she was the heiress to a substantial fortune left to her by her father.

Until now little more has been known about Elizabeth Charlton’s family, but a chance discovery in the archive of C Hoare & Co has enabled me to map an extensive family tree, and to disclose that at the time of her marriage she had, in addition to her grandmother, four aunts, a great-aunt and five cousins, and that her family’s history is intimately entwined with the activities of the British in India, including one of the most notorious nabobs.

The story begins in Liverpool, where Richard Aspinwall (Aspinwall Family Tree) married Elizabeth Stanhope. His wife was a descendant of the 1st Earl of Chesterfield, but otherwise the family was undistinguished. Their son, Stanhope Aspinwall (1713-1771), became a diplomat, and was Secretary to the British Embassy at Constantinople from 1742, British Consul in Algiers from 1752, and later Private Secretary to Earl Harcourt, Ambassador to France, dying in Paris on 17th January 1771. He married Magdalena Baptistina (1720-1771), who appears to have been Mexican – how they met is a mystery – and they had four daughters. In 1747 Stanhope must have feared for some reason that he was near death, and made a brief will in his own hand, leaving everything to his wife and trusting her to make suitable provision for their children; although he lived for a further twenty-four years, he never updated the will, and it was still in effect on his death in 1771. His widow barely survived him.

Stanhope Aspinwall’s two sisters, Frances (1715-1808) and Elizabeth (1717-1796), travelled to India as teenagers, and married at the age of twenty. Frances’ husband James Berriman was a naval commander in the service of the East India Company, and Elizabeth’s husband Charles Simpson was one of the Company’s clerks. Unfortunately, this was a time when the pressures of disease and climate took a heavy toll on young Englishmen – the average life expectancy was said to be ‘two monsoons’ – and both men died within a couple of years, leaving Frances with a daughter, also called Frances (1715-1808).

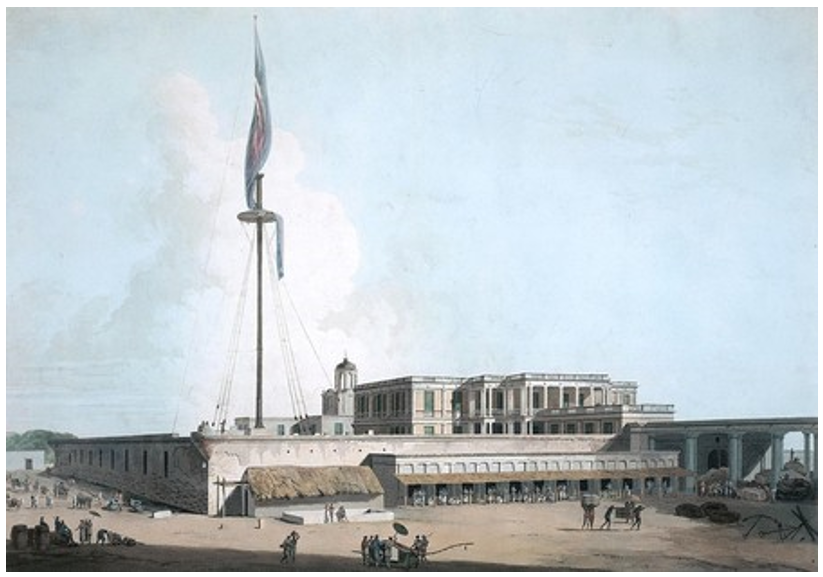

The two young widows soon caught the eye of other eligible bachelors: Elizabeth married Richard Prince, who by 1749 had been promoted to Deputy Governor of Fort George in Madras; three years later they returned to England.

[Fort George, Madras, in the mid-18th century]

Frances was not so fortunate: her second husband was William Henry Southby, a ship’s captain like her first. They had three children: Elizabeth (1742-1766) was born in Madras, but the family returned to England in 1750, where two more children were born. Their son John died shortly after his birth in 1753, but Catherine (1757-1805), who never married, lived a long life. They returned to India, where in September 1759 Captain Southby volunteered to command the ship Victoria on a voyage from Calcutta to Negrais, an island in the Irrawaddy river where the East India Company had a trading post. He took with him thirty-five Europeans and seventy Indians, and on landing the officers were invited to dinner by an emissary of the local ruler. They were suddenly seized by the servants and stabbed to death; their attackers then turned on the inhabitants of the British settlement and burned it to the ground. An accompanying ship, the Shaftesbury, was able to rescue some of them and recover Southby’s body, before returning to Calcutta with the dreadful news.

Frances Southby was now twice widowed, but she was not alone. On 22nd June 1756, at the age of eighteen, her elder daughter Frances Berriman had married Sir Thomas Rumbold (1736-1791). Rumbold entered the East India Company’s service as a writer in January 1752, at the requisite age of sixteen, but he soon switched to a military career. He was the sixth man in his family to go to India, following his grandfather, father, uncle and two brothers. Soon after his marriage, he accompanied Robert Clive to Calcutta, and was Clive’s aide-de-camp at the battle of Plassey. Resigning from the army, he joined the civil service as a Collector, which enabled him to cream off part of the land tax he collected on the Company’s behalf. He and two colleagues invested the proceeds in shipbuilding and trading in salt.

Frances Rumbold gave birth to three children: William (1760-1786), Frances (1762-1827) and George (1764-1807). She died giving birth to George, leaving her husband with three infant children.

The following year, when Robert Clive returned to India, Rumbold joined the Bengal Council, and was granted an extra share of the proceeds of the land tax. In 1769 he returned to England, by which time it was estimated that he was worth up to £300,000 (equivalent to £30 million today). He bought himself a seat in parliament, becoming MP for the notorious rotten borough of New Shoreham. In 1772 he re-married, to the daughter of the Bishop of Carlisle. However, he had left much of his fortune in India, where it was lost after the great Bengal famine of 1770, and he lobbied to be appointed to the governorship of Madras, which he finally achieved in 1778. The following year he was made a baronet.

Rumbold was a deeply unpopular governor, regarded as corrupt even by the standards of the time, and when he returned to England in 1781 there were demands for a parliamentary enquiry into the sources of his wealth, by now estimated at £600,000. He made attempts to become an MP, but his bribery of voters was so egregious that the results were set aside on more than one occasion; he finally succeeded in buying the pocket borough of Yarmouth in the Isle of Wight. He managed to avoid prosecution, and built a Palladian mansion at Woodhall Park in Hertfordshire, where he died in 1791.

There was a twist in the tale, since Rumbold (whose eldest son had predeceased him) had quarrelled with George, his other son by Frances Berriman, and cut him out of his will, leaving his entire estate to his second wife and their seven children. George Berriman Rumbold therefore had to make a living, and he became a diplomat. In 1804, at the height of the Napoleonic wars, he was the British representative in Hamburg, where on the night of 25th October he was abducted by a detachment of 250 French troops, his papers seized, and accused of conspiracy. He was taken to Paris but, after protests by the Prussians, was expelled to England.

George had in 1783 married Caroline Hearn in Bengal, and they had two sons and four daughters. These were Frances Southby’s great-grandchildren, and she was to leave them a substantial legacy in her will.

Find out more in Part 2 and Part 3.

Please note that all dates and location information are provisional, initially taken from the library and archive catalogues. As our section editors continue to work through the material we will update our database and the changes will be reflected across the edition.

Browser support: The website works best using the Chrome, Edge, and Firefox browsers on the PC, and only Chrome and Firefox on the Mac.